Unconventional warfare, or UW, is defined as activities conducted to enable a resistance movement or insurgency to coerce, disrupt or overthrow an occupying power or government by operating through or with an underground, auxiliary and guerrilla force in a denied area. Inherent in this type of operation are the inter-related lines of operation of armed conflict and subversion. The concept is perhaps best understood when thought of as a means to significantly degrade an adversary’s capabilities, by promoting insurrection or resistance within his area of control, thereby making him more vulnerable to a conventional military attack or more susceptible to political coercion. “UW includes military and paramilitary aspects of resistance movements. UW military activity represents the culmination of a successful effort to organize and mobilize the civil populace against a hostile government or occupying power. From the U.S. perspective, the intent is to develop and sustain these supported resistance organizations and to synchronize their activities to further U.S. national security objectives.”

…

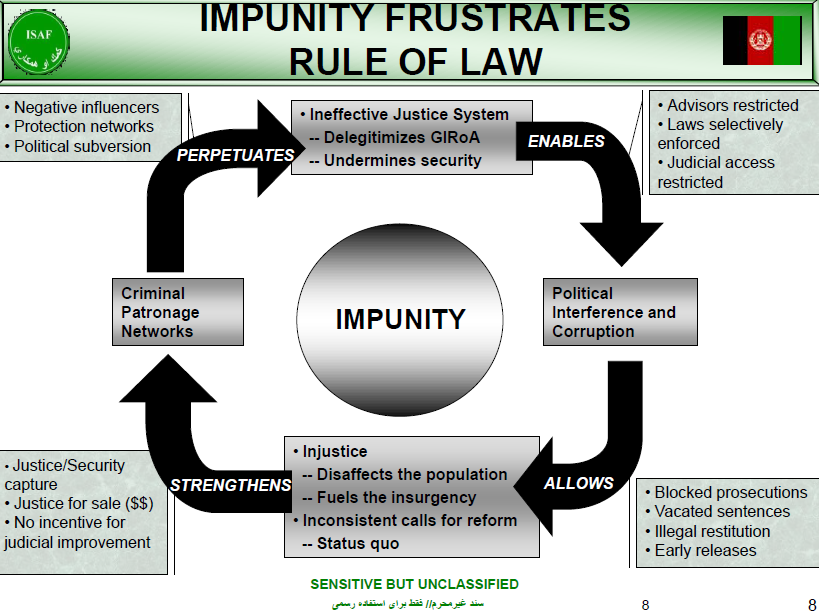

Enabling a resistance movement or insurgency entails the development of guerrilla forces and an underground, both with their own supporting auxiliaries. The end result comes from the combined effects of “armed conflict,” conducted predominantly by the guerrillas, and “subversion,” conducted predominantly by the underground. The armed conflict, normally in the form of guerrilla warfare, reduces the host-nation’s security apparatus and subsequent control over the population. The subversion undermines the government’s or occupier’s power by portraying them as illegitimate and incapable of effective governance in the eyes of the population. In order for an adversary to be susceptible to the effects of insurgency or resistance, he must have some overt infrastructure and legitimacy that are vulnerable to attacks (physical or psychological). In this respect the “target recipient” does not have to be a state government, but it does have to possess state-like characteristics (e.g. the elements of national power), such as those similar to an occupying military force exercising authority through martial law. It is not uncommon for military planners to overfocus on the quantifiable aspects related to the more familiar armed conflict and underfocus on the somewhat less quantifiable and less familiar aspects of subversion.

While different insurgencies are unique to their own strategy and environment, U.S. Army Special Forces has long utilized a doctrinal construct that serves as an extremely useful frame of reference for describing the actual configuration of a resistance movement or insurgency. This construct depicts three components common to insurgencies: the guerrillas, the underground and the auxiliary. Without an understanding and appreciation for the various components (guerrillas, underground and auxiliary) and their relation to each other, it would be difficult to comprehend the whole of the organization based solely on what is seen. In this regard, insurgencies are sometimes compared to icebergs, with a distinct portion above the surface (the guerrillas) and a much larger portion concealed below the surface (the underground and auxiliary).

…

The Guerrillas

Guerrillas are the overt military component of a resistance movement or insurgency. As the element that will engage the enemy in combat operations, the guerrilla is at a significant disadvantage in terms of training, equipment and fire power. For all his disadvantages, he has one advantage that can offset this unfavorable balance…the initiative. In all his endeavors, the guerrilla commander must strive to maintain and protect this advantage. The guerrilla only attacks the enemy when he can generate a relative (albeit temporary) state of superiority. The guerrilla commander must avoid decisive engagements, thereby denying the enemy the opportunity to recover and regain their actual superiority and bring it to bear against his guerrilla force. The guerrilla force is only able to generate and maintain this advantage in areas where they have significant familiarity with the terrain and a connection with the local population that allows them to harness clandestine support.

The Underground

The underground is a cellular organization within the resistance movement or insurgency that has the ability to conduct operations in areas that are inaccessible to guerrillas, such as urban areas under the control of the local security forces. The underground can function in these areas because it operates in a clandestine manner, resulting in its members not being afforded legal belligerent status under any international conventions.

Examples of these functions include:

• Intelligence and counterintelligence networks

• Subversive radio stations

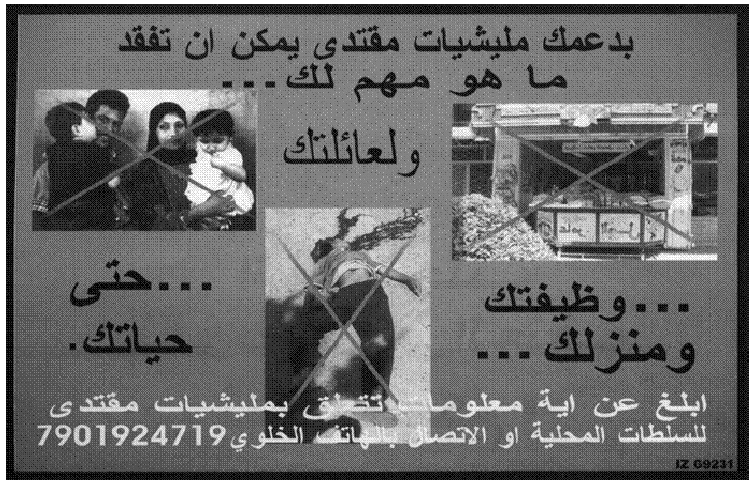

• Propaganda networks that control newspaper/leaflet print shops and or Web pages

• Special material fabrication (false identification, explosives, weapons, munitions)

• Control of networks for moving personnel and logistics

• Acts of sabotage (in urban centers)

• Clandestine medical facilities

Underground members are normally not active members of the community and their service is not a product of their normal life or position within the community. They operate by maintaining compartmentalization and having their auxiliary workers assume most of the risk. The functions of the underground largely enable the resistance movement to impact the urban areas.

…

The development of organized resistance in a territory must follow a carefully planned sequence of steps, each of which must be completed successfully before the following step can be safely taken.

1. Organization of clandestine networks. The first essential is to be able to move resistance organizers and propaganda material into the territory; support them clandestinely, and provide for continuing communications with adjoining resistance bases. These networks also pave the way for later active resistance by developing active support from a significant part of the total population.

2. Organization of intelligence and counterintelligence networks. No resistance organization can operate successfully unless it is fully protected by a deep intelligence screen. Equally, it is necessary to establish effective counterintelligence nets to verify every participant’s loyalty to the movement and, through penetrations into the enemy security services, to identify those who are acting as double agents.

3. Organization of local area commands in areas of favorable terrain. Such area commands will be the forerunners of later fully-armed guerrilla units, and will provide the transition between the entirely clandestine civilian organization and the mobile armed guerrilla force living in forests and other inaccessible areas. These commands will be given full responsibility for the organization of their geographical areas, including the organization of supplies, intelligence, propaganda and communications. As the area commands continue to develop, they may further subdivide the area into subordinate sector commands. These sector commands will carry the brunt of attacks against enemy installations and forces, while drawing support from the area commands.

4. The development of direct communications with the outside. At approximately this point in the development of resistance in the area, direct communication with the outside world can be established, although it may be established in some cases at an earlier stage.

5. Gradual development of free territory in the hinterlands. As the fighting units further develop in strength, it will be possible to establish relatively large areas that are normally free of any enemy troops and all enemy controls over the civil population. At this point, these “liberated” territories can begin to prepare and organize to replace the enemy structure on the completion of the conflict.

…

U.S. UW Efforts from 1951- 2003

U.S. Military and CIA in Korea (1951-1953)

The U.S. military was largely caught off guard by the conflict in Korea. Despite tremendous success during World War II, the capability to support resistance movements was almost completely removed from within the Department of Defense by 1950. A fraction of the capability was retained in the newly established CIA, but proved to be inadequate to meet the needs of a full-scale campaign. Overall this campaign effort was effective, but not nearly as effective as it could have been. The inability to establish sustainable guerrilla areas on the mainland hampered long-term operations. The U.S. provided personnel who were not familiar with the concepts and techniques associated with resistance operations. The military’s best attempt to find a matching experience set was to send basic-training instructors. Operations made wide use of displaced refugees as recruits and were generally launched from outside enemy-controlled areas and resembled temporary raiding parties.

The resulting operations caused the military to re-think its position on a military force trained for this type of operation. In 1952, the first official U.S. Special Forces organization was established. In 1953, some of the newly developed Special Forces deployed to Korea. However, they were not employed as intended and generally used as replacements.

CIA in Albania and Latvia (1951-1955)

The CIA used these opportunities to test theories for rolling back communist domination of Eastern Europe. These locations were chosen due to their relatively small size. Both efforts were failures. From these efforts the CIA theoretically learned three lessons. First, techniques used during wartime do not apply in peacetime (emphasizing the need for covert methods of operating). Secondly, tyrannical regimes that have had the benefit of years to consolidate power have a much greater hold over the population than a newly occupying power. Subsequently, there must be a weakness that can be exploited. This specifically equates to the ability of the state to exert control over the population and the population’s willingness to resist. Lastly prior to any guerrilla operations, a sufficient base of support must be present in the form of auxiliary and underground networks, although the least visible and understood, it is the most time-consuming and difficult to establish. Developing guerrilla elements is relatively easy; keeping them alive is much harder. Trying to jump ahead to developing guerrillas is like trying to build the upper floors of a house before laying the foundation.

CIA in Guatemala (1954)

In 1954, various influential businesses persuaded members of the media as well as members of the U.S. government that the Arbenz government, which was the elected government of Guatemala, was leaning toward communism. The U.S. government, through the State Department and the CIA, convinced several senior Guatemalan military officials to overthrow Arbenz’s government. This effort was supported by a highly successful psychological campaign that portrayed the overthrow as part of a much larger movement. Although widely suspected, the U.S. government’s hand in this effort remained ambiguous for a couple of years until it was finally exposed as the follow-on governments were accused of being inept dictators by the Guatemalan population. Although often portrayed as a success, the hindsight of history now reveals the Guatemalan operations were in fact “shameful, particularly so because the five decades of governments that followed the 1954 coup were far more oppressive than Arbenz’s elected government. Aside from the morality, there were other unfortunate legacies of the Guatemalan “success”. Allen Dulles used it as a model in advising President Kennedy seven years later to pursue the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.” The Guatemalan effort serves as an example of tactical success in isolation of any wider sound strategy, particularly in the form of long-term effects on a region. This effort coupled with the coup of the elected Mossedegh government in Iran (1953) provided a strong argument to de-legitimize any U.S. claim to support democracy for the remainder of the Cold War.

CIA in Tibet (1955-1969)

While this campaign was very well executed, no level of tactical success in Tibet could defeat the Chinese. The National Volunteer Defense Army (NVDA) did successfully delay the Chinese victory by several years. In 1960, the first U2 aircraft was shot down. Although not related to the covert support efforts, the subsequent compromise of U.S. clandestine overflights of communist territory caused the U.S. President to suspend all further clandestine overflights, which essentially crippled the air resupply to the Tibetan guerrillas. A year later, the catastrophic failure of UW efforts in Cuba nearly ended the Tibetan program. The last resupply airdrop to Tibetan resistance forces took place in 1965. Although the U.S. ceased all support to the Tibetan resistance in 1969 as a condition for eventually establishing diplomatic relations with China, the Tibetan resistance continued to resist into the 1970s. Two lessons can be drawn from the Tibetan efforts. As an alternative to prior U.S. efforts where advisers infiltrated into the combat area, in this effort selected personnel were extracted, trained and reinserted with reasonable success. The nature of the offensive operations in this type of campaign is different compared to operations that culminate in support of a TBD D-day. Without the eventual introduction of conventional forces (i.e., a D-Day) the combat operations need to be sustained for an undetermined period of time and therefore conducted in a manner that does not compromise the supporting resistance infrastructure.

CIA in Indonesia (1957-1958)

Fearing that the Indonesian government was leaning toward communism, after a declaration of neutrality, the CIA supported several Indonesian military officers who claimed to control a rebel army made up of former military units. During this operation, the CIA chose to employ refitted B-26 bombers and P-51 fighter aircraft flown by mercenaries from various countries. The rebel army had little popular support among the population while the Indonesian government still held control of the majority of its military. During the course of the support effort, direct American support was exposed several times causing embarrassment to the United States. This situation finally came to a head when a B-26 flown by an American CIA contract employee was shot down and the pilot was captured by Indonesian forces. Although the CIA was confident that no link could be made between the U.S. government and the pilot, he in fact had documents on him that indeed did link him to Clark Air Force Base. The incident had been a major scandal for the Eisenhower administration. Soon after the scandal broke, the CIA ceased all support and the Indonesian government crushed the rebellion with conventional military forces. A particularly interesting point in this case is that Indonesia was not considered a belligerent state when the decision was made to support the rebels. The U.S. State Department maintained relations with the government and had an embassy in Jakarta during the operation.

CIA in Cuba and the Bay of Pigs (1961)

The CIA applied a variety of the nine-phase model, consummate with covert operations, but attempted a culminating D-day style uprising rather than sustained guerrilla warfare. There were some reasonably successful efforts to develop underground elements, but these efforts were not coordinated with the larger campaign. They did not employ appropriate techniques to conceal the operation or the U.S. participation. The “resistance movement” was generally manufactured, rather than fostered from an already existing one in country. Lastly operational security in the United States was a complete failure.

The lessons of the Bay of Pigs are as follows:

• Resistance forces require clandestine infrastructure and support mechanisms.

• These operations require planners and advisers who understand the dynamics of insurgency/ resistance operations (including guerrilla warfare and underground operations and how they integrate with each other).

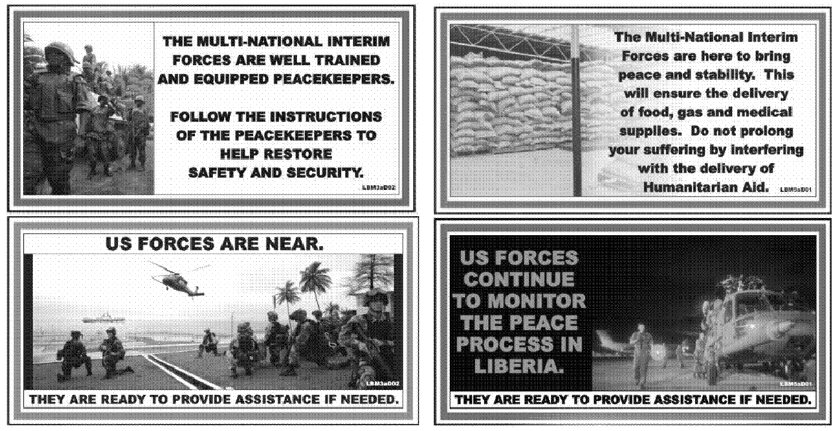

• When there is a population involved, the psychological piece (i.e. propaganda and subversion) may be more important than the physical piece (guerrilla warfare).

• This type of effort requires the ability to conduct the full spectrum of nonattributable psychological operations in conjunction with the physical piece.

• Any organization involved in UW (particularly peacetime) needs a comprehensive understanding and process for oversight, C2 and OPSEC for covert and clandestine ops.

CIA and Special Forces in Laos (1959-1962)

In 1959 the United States began a secret program called White Star. This opera tion was coordinated in conjunction with the French government to train Laotian Army Battalions. Personnel came from the 1st and 7th Special Forces groups. In December of 1960, a group of Laotian paratroopers attempted a coup d’etat that caused the withdrawal of the French advisers, whom had previously restricted American military involvement to the role of trainers. During the counter coup, Special Forces personnel advised the remaining parachute forces to rout the rebel paratroopers, winning great favor with the Laotian government. By 1961 the original contingent of nine ODAs had grown to 21 ODAs and the effort expanded to include an advisory role. The counterinsurgency efforts also included training for selected tribal elements in civil defense. A concept was developed to expand the tribal operations [covertly] to the rural areas in northern Laos parallel to the North Vietnamese border. Special Forces also undertook two major unconventional programs in northern Laos (as compared to the other counterinsurgency programs). Both programs concentrated on training minority tribal groups as irregular forces capable of conducting guerrilla warfare across rugged terrain or behind the enemy lines. The Kha program, the second unconventional training activity, was designed by Special Forces to use the various Kha tribes in harassing and raiding enemy rear bases and installations especially along the Ho Chi Minh trail, the primary overland North Vietnamese resupply route across Laos into South Vietnam and Cambodia. Unfortunately higher authorities refused to adopt the Special Forces suggestions regarding the newly created guerrilla movements and due to political decisions the Meo and Kha programs never realized their full potential. After 1962, the effort was dramatically reduced when Laos declared its neutrality. While the Special Forces involvement ended, U.S. support continued covertly by the CIA to General Vang Pao’s “Army Clandestine” for another decade.

The counterinsurgency programs in Laos are sometimes misrepresented as UW. The counterinsurgency efforts conducted against the Pathet Lao in southern Laos were significantly different from the proposed UW efforts envisioned for northern Laos and North Vietnam. The proposed UW efforts were intended to interdict and harass regular North Vietnamese forces who were occupying Laotian territory in order to establish supply networks into South Vietnam which later became the Ho Chi Minh trail.

CIA and Special Forces in North Vietnam (1961-1964)

In 1960, the CIA began attempts to establish agent networks within North Vietnam. The program, called Leaping Lena, was highly penetrated by double agents and never produced any viable results beyond a handful of questionable agents. The hopes of conducting UW against North Vietnam had diminished by 1964 when the military assumed control of the operation. The Special Observations Group’s or SOG’s actual name had been UW Task Force. The Special Forces concluded Leaping Lena by parachuting the questionable trainees over North Vietnam and terminating further support. From this point on operational efforts focused on portraying a false resistance movement intended to confuse the North Vietnamese.

The program shifted to covert coastal raids (similar to North Korea) and covert reconnaissance and interdiction missions into Laos and Cambodia. Special Forces in

South Vietnam (1957-1975)

As a result of the increased concern over communist subversion in Vietnam and at President John F. Kennedy’s insistence, SF added COIN to its list of missions in 1961, making a significant point that it is different from UW and not a subcomponent of it. The majority of Special Forces efforts in South Vietnam were not UW but rather COIN, specifically the Civilian Irregular Defense Group, or CIDG, the Provisional Reconnaissance Units, or PRU, and Mike Forces.

The CIDG were indigenous irregulars who provided a vital counterinsurgency role of area denial by securing hamlets.

The PRU were indigenous platoons developed as part of the CIA Phoenix program. These elements identified insurgent support infrastructure (or underground and auxiliary members). This effort could be called counterterrorism, or counterinsurgency. SOG also developed platoon- and company-size strike forces called Mobile Guerrilla Forces and Bright Light teams. The Mobile Guerrilla Forces acted as quick-reaction forces for recon teams in contact with Viet Cong elements and the Bright Light teams conducted raids to rescue allied prisoners and downed air crews. The Mobile Guerrilla Forces conducted four static line jumps during their operations and the Bright Light teams conducted nearly 100 raids (in S. Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia). While these efforts utilized recruited indigenous personnel, they were not considered UW. In 1970, this program disbanded and transformed to an adviser program for Vietnamese and Cambodian counterguerrilla forces.

See Colonel (R) Al Paddock’s (the author of U.S. Army Special Warfare and Its Origins) comments regarding a review of Imperial Grunts (and the misuse of the term UW) in the March-April 2006 Special Warfare. Paddock, a Special Forces veteran of SOG and the CIDG mission stated, “In truth, the mobile guerrilla forces can be more likened to World War II long range penetration units such as Merrill’s Marauders or Wingate’s Chindits. This is not to say that the Mobile Guerrilla forces did not perform useful or heroic missions. They did, but not as guerrillas.”

CIA and Special Forces in Nicaragua and Honduras (1980-1988)

The United States supported various resistance groups that opposed the socialist Nicaraguan Sandinista government. These groups, which operated from Honduras and Costa Rica, collectively became known at the Contras. RAND after action reviews from this covert operation criticize it for being artificially manufactured and not having legitimate support inside Nicaragua. “This effort was developed almost entirely along military lines and advisors lacked practical understanding of the requirements to develop and run an insurgency.” (U.S. Support to the Nicaraguan Resistance, 1989 and The U.S. Army’s Role in Counterinsurgency and Insurgency, 1990). The Contras have been compared to paid mercenaries with no real political component and connection to the population. This may partially explain the lack of guerrilla bases inside Nicaragua. The other part of the explanation comes from the strength of the government counterguerrilla forces. The Contras would not have survived without the safe havens across neutral borders. Ultimately the covert operation, which became widely exposed due to the Iran-Contra scandal, ended badly for the U.S. government and caused feelings reminiscent to the post Bay of Pigs-era regarding covert support to insurgents.

CIA and Special Forces in Pakistan and Afghanistan (1980-1991)

While this covert effort remained primarily training and material support, it grew to the point that the potential risk of providing indigenous guerrillas with U.S.-man ufactured lethal aid (such as Stinger anti-aircraft missiles) became acceptable. U.S. personnel established supporting bases in Pakistan (following the nine-phase model mentioned previously). There are several lessons of the operations in Afghanistan. Covert operations of this nature require neighboring partner countries to develop support bases. This necessity causes a level of compromise in U.S. objectives. Pakistan controlled the distribution of U.S. support to rebel groups and subsequently was able to alter the balance of power among resistance group in Pakistan’s favor. Afghanistan highlights the importance of maintaining perspective of long-term goals and not allowing enthusiasm to overtake decision making. The importance of a feasibility assessment before the decision to throw support at a group can’t be overemphasized. Any support will change the balance of power and dynamics of the region. When a group is supported, engagement should continue until post-conflict stability is achieved. The Taliban came to power because the U.S. ceased support to Northern Alliance troops and other Islamic nations did not cease their support to these radical groups.

The sensitivity of these types of covert operations demands that operational commands interact directly with the national command authority and not through various “go betweens” in a long military chain of command.

Cold War Contingency Plans for Scandinavia and Europe. (1952-1989)

Although not executed, it is worth including the contingency plans that Special Forces would have implemented in the event of escalated hostilities in Europe during the Cold War. There is little debate as to the nature of what SF was prepared to do in this event; unfortunately, these plans count for little as they fade farther away with each passing day. There would be much value to declassifying some of this information for the betterment of the military’s knowledge. At the height of the Cold War, 10th Special Forces Group remained prepared to employ 50 plus detachments across the whole of Europe. In addition to 10th SF Group, Det-A, although manned with SF Soldiers not officially part of 10th SF Group, remained prepared to conduct UW with its six detachments specifically in the urban areas of Berlin and northeast Germany.

Kuwait (1990-1991)

Following the Iraq invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, several isolated pockets of Kuwaiti resistance formed. Although the U.S. was in contact with elements of the Kuwaiti government in-exile in Saudi Arabia, efforts to support and coordinate the resistance forces was poorly integrated with the main military campaign planning. Planning efforts were too little and way too late. Although Kuwait offered little favorable terrain to support resistance operations, ad hoc resistance forces did operate without U.S. support until their eventual destruction. The operation may have proven unfeasible, but other circumstances rendered that debate irrelevant. Post-war after-action reviews indicated a general lack of organic capability, a lack of understanding of the requirements for supporting a resistance throughout the Department of Defense (to include special-operations forces) and a lack of synchronization between DoD and the interagency.

You must be logged in to post a comment.